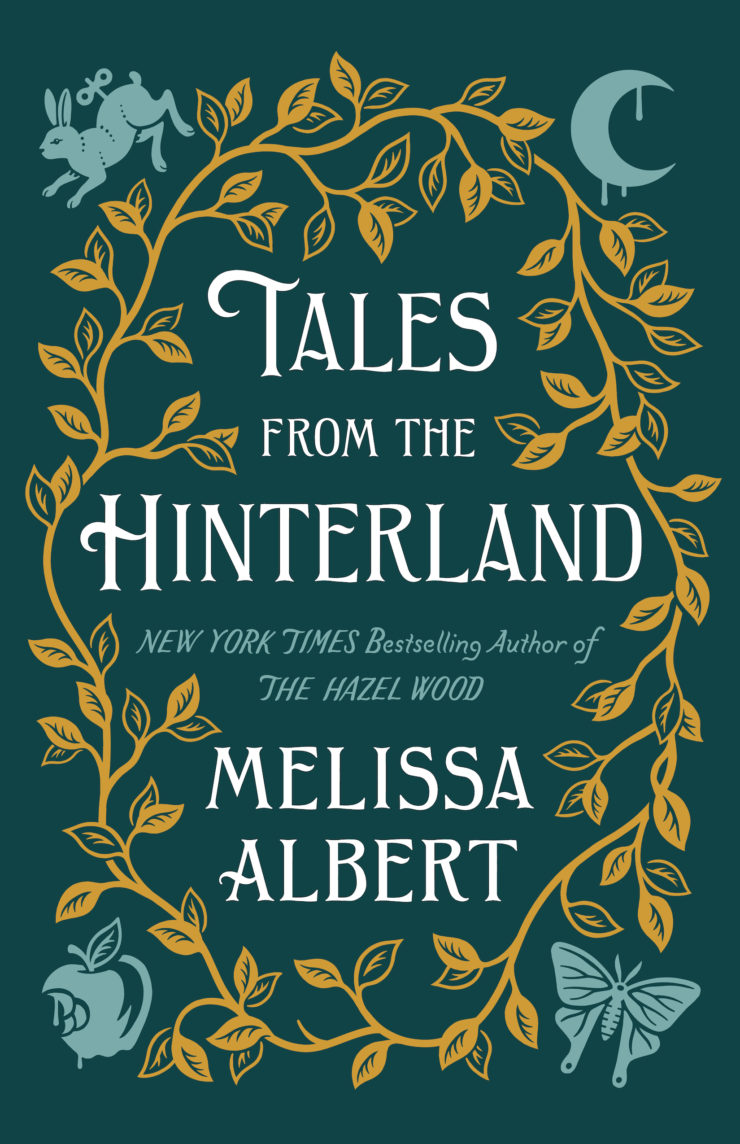

We’re excited to present the cover and an exclusive story from Melissa Albert’s Tales from the Hinterland, a follow-up to The Hazel Wood series, featuring all of the long-awaited dark and twisted backstories to all of its fairy-tale characters. Tales From the Hinterland releases January 12, 2021 from Flatiron books.

Before The Hazel Wood, there was Althea Proserpine’s Tales from the Hinterland…

Journey into the Hinterland, a brutal and beautiful world where a young woman spends a night with Death, brides are wed to a mysterious house in the trees, and an enchantress is killed twice—and still lives.Perfect for new readers and dedicated Hinterland fans alike, Tales from the Hinterland is a gorgeously illustrated collection of the twelve original stories that frame Melissa Albert’s beloved bestsellers, The Hazel Wood and The Night Country.

Buy the Book

Tales From the Hinterland

Melissa Albert is the New York Times bestselling author of The Hazel Wood and The Night Country. She was the founding editor of the Barnes & Noble Teen Blog and has written for publications including McSweeney’s, Time Out Chicago, and MTV. Melissa lives in Brooklyn with her family.

Twice-Killed Katherine

An enchanter lived in a house with rooms beyond counting, in the shadow of an ancient oak. He had a string of wives behind him and as many children as his house had doors, because when he was young he’d learned the secret of long life. Using sweet smoke and words stolen from a witch, he’d coaxed his own death from his body, hidden it in an acorn, and buried the acorn below his window. The branches of the oak that rose from the acorn still tapped against the glass, but the wise old face in the tree’s trunk that once spoke to him had long ago gone quiet.

The enchanter, rich and as handsome as he’d been when he seduced the witch who gave up the words, had no shortage of wives when he wanted them. His latest was beautiful and young and prouder than he’d given her credit for, with a will nearly as strong as his own. She was determined he would end his dalliances with the servants and in town, and fixed her heart on making his life a misery if he didn’t. And so, when the stable master’s wife told the enchanter she was carrying his child, he was set on keeping it a secret.

After receiving word that the midwife had been sent for, the enchanter dispatched the raven that was his familiar to stand watch at the stable master’s window. The laboring woman saw the black bird peering in and was afraid, for herself and the child she carried. When the baby came it was red-haired and blue-eyed, with a hard chin and blade-cut mouth, every inch the enchanter’s child. But the stable master’s hair was ruddy enough, and a purse of gold convinced him to accept the girl as his own.

She was called Katherine, and grew up in solitude. Her mother resented being closeted with a baby in their crude quarters, and the stable master didn’t care for children. Katherine would have been very lonely had she not learned, early on, that she had a powerful affinity for growing things. She gave flowers new ambitions, convincing them to creep free of their beds and up around her windowsill. She coaxed a bounty from her mother’s mean kitchen garden and made the grass around their door grow thick and high, never suspecting she was drawing from the slipstream of magic that ran in her blood.

She was always fascinated by the enchanter’s oak tree. His servants knew without being told that the oak was not to be disturbed. Never pruned nor otherwise tended nor walked beneath. Even its shade was shunned, having an unsettling texture to it, that of something you could peel back and fold or step into and be lost completely.

Katherine did not share their fears. When she was old enough to crawl, she crawled toward the tree. When she learned to run, she ran to it. Her miserable mother always caught her, until Katherine grew old enough to care for herself and her mother gave up trying.

“Go,” she said, “and curse yourself if you wish. Let the old tree swallow you, or the ground, for all I care. Let the enchanter himself find you and beat you, if it teaches you at last to be still.”

Katherine took her mother’s abuse in silence, as she always did, waited till the woman wasn’t looking, and fled to the tree. Over the creek, past the stables, through the enchanter’s gardens, to where its shadow spread over the grass like a pool of black water. It was cool and dark and slightly binding, clinging to her skin. She laid a hand on its bark and felt it grow keen beneath her fingers. It was the same feeling she had when making a tomato plant grow out of season, or convincing a bush that bore only leaves to bud with flowers.

She put a foot on the trunk and settled her fingers in its furrows. She began to climb.

Though the enchanter’s body was young, his mind was old beyond reckoning. He looked at the age-twisted oak sometimes and marveled that he’d known it when it was a dream inside an acorn. His mind still ran like quicksilver, still sparked like water over rocks in sun, still wondered and lusted and questioned and raged, but sometimes when he looked at the tree’s scarred trunk he felt very old indeed.

It was one such time when—gazing into its shifting leaves—the enchanter saw another face peeping out at him from among them. It was sharp and fearless and a cunning kind of quiet. It looked just like his own. Having long forgotten about the stable master’s wife and his little red-haired by-blow, the enchanter was startled, a thing he very rarely was.

“Who are you?” he asked, in a voice that sounded less than commanding. “Are you my death returned?”

The creature in the tree said nothing.

“Do you come to remind me of my own mortality?” he said. “Go back, feed the oak, and be patient. I have much work to do before I have need of you.”

Katherine watched him in startled silence, and he might have turned away still believing her to be his long-deferred death, having crept up out of the acorn to glare at him. But just then she lost her footing. As she clung to the branches, her face colored with surprise, and he realized she was quite human. A child. And he remembered the baby who had looked at him with such composure more than a decade ago, when he went to strike a deal with the cuckolded stable master. In one motion, he lunged over the windowsill—his body stretching unnaturally, arms long as branches—and pulled the girl into his house.

Katherine knew when to be quiet. She knew how to stand very still, so she no more caught the eye than a footstool did, and if she were to be kicked or slapped, it would be with the impersonal violence enacted upon an inanimate thing.

She stood before the enchanter, in his rough brown robe with its sleeves pushed up and the raven on his shoulder. His face was so exactly like her own that it answered a question she’d never thought to ask.

“Are you not afraid of my tree?”

His voice was stern, but she sensed he was pleased by the notion. She shook her head.

“They say the touch of its shade will flatten you like a flower and deliver you straight to Death. They say the nod of my head could flay you where you stand, that my voice alone is deadlier than a goblin’s kiss. Are you unafraid, or just foolish? Do you not believe what they say about me?”

Katherine’s face was composed, but he saw the nervous motions of her fingers. Then he saw what was happening beneath them: flowers, growing from a crack in his windowsill. They budded and bloomed and died and began again. She spoke no words, looked only at him, but under her hand there was magic.

When his children came of age, the enchanter tested them to see if they’d inherited his abilities. On finding them lacking, he sent them out into the world, to marry or seek their fortune or do whatever they wished, so long as they never returned to his house. Katherine was the first of his offspring to have his gift, and he meant to teach her.

That first day he didn’t let on to her that he saw what she was doing, and that its name was magic. Instead he let his oak lean close to the window, so she could go out the way she had come. He meant to prepare his workshop for a student, who would, in time, become an enchanter herself, one he could hold in his thrall and use as a secondary source of power. It was lucky she was a woman, and simpler to sap.

When his preparations were made he sent a servant to fetch her, and learned she could not come. The wasting sickness that paced the nearby town had reached the stable master’s house, and Katherine had fallen ill. He worked out how to save her, brewed a tincture that could do it, but when he carried the medicine to her cottage she was already dead.

The enchanter stood at her bedside, looking upon the withered little face so much like his own. Her mother gaped at him, dry-eyed and very far from the fox-pretty maid he’d once sported with in the rooms of his house. Something moved in him, a weakness he hadn’t faced since divorcing himself from death: grief. For just one moment, he mourned the dead girl in the bed. And before he could think better of it, his hands were weaving the air, turning it thin and bright and unbreathable, as he worked a heavy enchantment. It made his bones creak and brought out lines of silver in his hair. It made his oak tree drop its leaves and groan low, the sound of it running through his house and filling its occupants with dread.

He could not return the girl’s life to her: it was gone. He could not take her death away: she’d already spent it. So he gave her a different kind of gift. Her body was freshly dead, still warm. And where there’s warmth, there is hunger.

He gave that hunger eyes. He gave it will. He shaped its formless turning into something pointed as a dagger. That dagger cast about the room, seeking the life it longed for. Drawn in by the beat of blood and breath and the high curdling flavor of fear, it fixed itself on Katherine’s mother, fitting its invisible mouth to hers and drawing out her life. As the woman’s hair faded to ash and her bones curled in like fingernails, the girl on the bed shifted. She moaned. She opened her eyes.

Katherine was not unchanged by death.

When her body uncaged her mind, it went far below. She found herself in Death’s kingdom, that airless realm of mineral trees and floors of blue agate, where there is no sun or sky, but a distant pearly ceiling.

She reached for her magic, that green-fingered ability she drew on without knowing its name. In a land where nothing grew, she couldn’t find it. She wanted to panic or grieve, and could discover the capacity for neither. Death’s kingdom was no place for rosebuds or high emotions. Katherine felt herself shrinking in its fist, felt the shearing of her power and the ebbing of her fear, when suddenly she was blinking, breathing, crying out on her own hard bed, in her own ravaged body. Life buzzed inside her like a fly seeking escape, throwing itself at her borders.

She didn’t know the life was her mother’s. The enchanter told her nothing about it. But she was never easy with that life inside her. It was a flame too long given to flickering. And while she forgot her hour in the land of Death, it had left its mark on her. Her bright hair now ran black. The gardens she tended grew florid with red flowers and dark fruit that numbed the tongue and drugged the senses. All the fresh green things she tried to grow collapsed into rot.

Katherine was not the only victim of the wasting sickness. The enchanter’s own wife walked into Death’s kingdom three days after Katherine left it. With no woman left to appease, the enchanter brought his illegitimate daughter to live inside his house.

Her power grew by the day. She could make things move outside of their nature, she lit candles with a snap. She made her father’s eyes ignite with a radiant greed, though at first she saw only the radiance. Dreamier than she’d been before dying, she was still quick-minded, clever, and keen to learn.

Katherine grew up in pieces. Her limbs then her face then the rest of her, until all at once she was a woman, legs too long beneath the hems of her dresses and hair still braided back like a girl’s, framing the fine gull curves of her bones. Proud not only of her skill but of her beauty, the enchanter had a new wardrobe made for his daughter and hired a maid to do her hair. And on a spring day so fresh and soft and wet it seemed it could break apart in your hands, he packed her into his fine carriage to show her off to the only one in the world whom he counted as his equal.

The man they were visiting was another enchanter who’d deferred his death. Though the two old foes despised each other, they gilded their envy and scorn with fine words, meeting every ten years to exchange gossip and brags. While the other enchanter traveled widely and took many protégés, Katherine’s father lived his lifetimes in one place, and had never before had a student worth teaching. He wished to show his friend and enemy that he had sired a true enchanter.

On the day they rode out, a week of heavy rains had sent the river welling past its shores, turning the road into a ribbon. The water carried in its arms not just fishes and fallen leaves but ladies’ shoes and gemstone buttons, polished bones still sighing, a cradle and a wooden doll with no mouth, a dead rivermaid wrapped in weeds. Katherine gazed into the waters, dreaming. When they arrived at the other enchanter’s house, in a prosperous town on the banks of the river, she felt as out of place as the mouthless doll.

The other enchanter’s face was even younger than her father’s, frozen forever at twenty. He had yellow hair and eyes as old and cold as the stars. When he laid them on Katherine their force was such that she startled, a poppy blooming in her right hand and a black plum in her left.

The beautiful man took her plum and bit into it, letting its juice run into the golden hairs of his arm. He licked it off and smiled at her.

Katherine took pains not to be alone with her father’s rival. His eyes followed her about the room, sliding over her skin like willow whips as he watched what she could do, in the exhibitions of ability her father insisted she perform. They were to stay with this enchanter for a week, long enough for the two men to deride mutual acquaintances, exhaust their boasts, and finally grow so disgusted with each other they couldn’t bear to meet for another ten years.

Four days had passed when the golden-haired enchanter let himself into Katherine’s room. It was late, but she heard his key in the lock she’d so carefully thrown, and was sitting up in bed when he opened the door.

“What will you do?” he asked playfully, when he saw her expression. “Throw plums at me?”

She did. She brought all her magic to bear on confounding his path between the door and the bed. But she was young, and he was ancient, and her power to his was as a drinking cup to the sea. Or so he thought, and she believed.

He reached her, still laughing, his skin glowing in the candlelight. The feeling of his magic overpowering hers was a press at her temples, a cold absence in her hands. When he seized the front of her nightdress, she abandoned magic and went after him like a cat fighting its way from a sack. Her nails found his cheeks, her teeth his throat, her knee the place between his legs. With a curse he rendered her still as the dead, nothing moving but her eyes and her tears and her drumming heart.

No violation was enough for the wound she’d dealt his towering pride. He took his knife from his loosened belt and ran it down the side of Katherine’s face as steady as a finger, watching her eyes widen in agony. Maybe it was the pain that allowed her to move just for a moment, long enough to lift her head and spit in his face.

When her spittle hit his cheek, his mind was turned from thoughts of lust. He stopped caring whose daughter she was, and what the cost might be if he broke her. He pressed his thumbs to her neck, slippery with blood, and squeezed.

“In my own house,” he hissed. “You bastard girl, you witch, you vile thing.”

Katherine’s vision ran with bubbles like black Champagne. She heard a voice in her ear, low and triumphant. I have you, Death said. I have you again.

Then the dark wrapped her up completely and she stood once more in that silent underground land that smelled like nothing and glittered with precious ore. But the place where her stolen life had lodged was empty again, gaping like a throat and made willful by magic. As Katherine looked about herself below, her hungry body stole the life from the golden-haired enchanter above.

So intent was he on killing her, only death could loosen his hands from her neck. She woke soaked through with blood from her wounded face. The enchanter’s body lay cooling on the floor.

It was luck that made her father find them before the servants did. The man was not entirely insensible to his old foe’s attentions to his daughter, and came too late to look in on her. When he saw the other enchanter dead and Katherine alive beside him, he paused for just a moment, his face showing more cunning than regret. Swiftly he packed their belongings, and a number of the other man’s treasures besides. Before the sun had risen, they were on the road toward home.

If Katherine’s first death left its film on her skin, her second dragged behind her like a mantle. Her footsteps made no sound, as if she walked again in the noiseless realm she remembered only in sleep. Her black hair blazed with a sharp white stripe.

Her face healed poorly, the scar left by her attacker’s knife clotting at her chin like candle wax. The enchanter could have healed it, but a scar was no barrier to magic, so it didn’t occur to him. Katherine might have removed it herself, but chose instead to grow accustomed to her altered reflection.

More than that had changed. While her father treated her as he always did, she saw different things in him now. When he smiled, she sensed his hunger. When he touched her, rarely—a tap on the hand, fingertips on her shoulder—she felt the faint buzz in it, not of love or affection but something darker, deeper in the bone. She could hardly bear his nearness.

Twice dead now, Katherine knew herself to be a thing that blocked the light. When her father took her to town, conversations cut out and laughter went cold. The townspeople feared the ageless enchanter and his heavy raven and his unspeaking mirror, the daughter who walked at his side. Her shadow had something of the oak tree’s about it, a depth and weight that made the unmagical shrink away.

She wondered, still, about the oak tree. She’d never forgotten the words the enchanter said to her as she perched like a bird in its branches. Are you my death returned?

Often she walked beneath it, letting her shade run into the oak’s like ink. The wizened face in its trunk had stilled its tongue many lifetimes ago, but before that day the enchanter leaned heavily on its counsel. It wasn’t until a night in Katherine’s nineteenth year, as she ran her curious fingers again over its features—the wide mouth, the eyes obscured by ridges of brow, the nose a mossy furrow—that it shifted from its heavy sleep.

“Daughter,” it said. “You are one like me.”

Out of respect she snatched her fingers back, but felt no fear. “How so, grandfather?”

“You and I are Death-fed.” Its bullfrog lips pursed. “My sap, your blood, are springs fed from Death’s own river.”

“What does it mean to be Death-fed?”

“It means peace will elude us, but have faith: it will be ours.”

“I don’t understand.”

The oak tree sighed, a heavy, gusting breeze that blew green leaves into her hair. “I grow weary, my child. I would like, at last, to break my bond with the enchanter. To sleep without cease. Will you help me?”

“I know nothing of death,” said the girl. “Only that I’ve escaped it.”

The oak tree knew that Katherine’s living mind could not hold the glimmer of death too long in its waters, and chose his words carefully.

“There is no escape from Death, only delay. And you know more of dying than you remember. To help me, if you’ll help me, you must seek out the witch from whom your father stole the words—those that allowed him to delay his death. Will you do this?”

Katherine looked at her father’s window. The shade was drawn and its edges lit, not with the yellow of candlelight but the blue of magic being worked. She shivered to think of his scent when he drew too close. Clove and attar of roses, cloaking the sulfur-and-bitters tang of enchantment. His stippled jaw, the faint lines at his eyes that never deepened. When he’d found her bleeding in bed at the hand of his rival, in that beautiful house in that prosperous town, he’d spared her only the briefest look, and a handkerchief to press to her riven face.

“Yes, grandfather. I will.”

Only one path led to the witch’s cottage: the white road laid out on the sea when the moon was one day from full. The witch had married a Tide when she was young, and though the marriage didn’t last, the Moon had allowed her to keep the cottage that was her wedding gift.

“Be unafraid,” said the oak, “and you will find the path grows firm as stone beneath your feet. Long has the witch craved vengeance on your father. She will not hesitate to help you.”

Armed with cloak and boots, a knife and her magic, Katherine left her father’s lands to seek the witch and the words. She knew the sea lay past the edge of town, close if you had a horse and far if you didn’t. On foot it took her four days to reach its shore. When she did, the new moon was rising, throwing filings of silver over the water.

Katherine sat on the sand watching moonlight break over the top of the sea. A coracle bobbed among the waves, the fisherman inside it casting his line into the salt. It went taut and, arms straining, he reeled in a piece of living light, wriggling like a worm as it came loose from the water. Again and again he cast his line, until he had a whole bucket of squirming silver. Then he poled to shore, climbing out to pull his vessel onto the sand.

He was broad but not tall. His hands were nimble and his dark skin scored with a crosshatch of scars, over his arms, neck, face, as if he himself had once been caught in a net. He didn’t look at Katherine as he busied himself over his bucket.

She’d spoken to no one since her conference with the oak tree, sleeping in secret places and staying hidden when the sun was out. But her voice sprang free of her now.

“What do you use to catch moonlight?”

A smile spread like butter over his scarred face.

“Damselflies.”

“What do you do with it?”

“Sell it to queens, to garnish their gowns.”

He was lying, she’d learn later. He was teasing her. The moonlight could be fermented with honey to make wine. It could be mixed with milk in a bath to soothe old bones. If you added it to lamp oil, your lamps burned brighter, longer, and kept ghosts away. There were many uses for moonlight harvested from the Hinterland Sea.

Katherine learned them all, in the fisherman’s cottage on the shore. When she married him, a month after they met, they drank moon wine to celebrate. And when her belly swelled with pregnancy, he rubbed moonlight in fish oil over her skin to soften it, and over her scar when it ticked with old pain.

Many months had come and gone by then. On the night before the Moon was at her fullest, Katherine always felt a pang, remembering her promise to the old oak. But what was one woman’s lifetime next to the life of a tree? She would seek out the witch when she was old. She wouldn’t forget the oak tree’s wish.

Her labor began with a wrench and a rush of blood.

Katherine thought it would be easy, that her magic would smooth the birth along. Her husband had attended the births of animals both larger and smaller than she, and he thought they needed no midwife. Both of them were wrong.

The baby fought against the birthing. Katherine’s body fought back, and it wasn’t clear who would be the stronger. Katherine lost blood, more of it, too much. The voice was in her ears again, the voice she hadn’t heard since the golden-haired enchanter laid his hands on her throat. You are mine again, Death whispered. Here I am to catch you.

In the end the baby was stronger than its mother, and Katherine’s life gave out. No sooner had she touched down on Death’s cold road than her body was reaching for a life that could bring her back. Her baby was close, so close, its fierce little body still nested inside her. Its life flowed like sap into Katherine. She was empty-eyed and still in her birthing bed, then alive again and screaming, as her husband slid his hands into her womb to pull the child free.

It slipped out gray-faced, with its parents’ dark hair. Katherine and her fisherman wept over it, his face in her shoulder and their hands on the child. But the baby’s thieved life was small and unsteady. Like all those newly born, it kept its toes dipped toward death. Katherine’s body, weakened by blood loss and aflame with grieving and infection, extinguished it.

Her husband’s life was stronger. With the will she could not control, gifted to her by her father’s dreadful magic, she took it.

Twice-killed again, alive once more, Katherine lay on bloody sheets, the baby stiffening on her belly and her husband’s body slumped over her shoulder.

A long time passed. She knew she must move but could not. Her hands that could birth dark fruits, fleshy flowers, lay still. Her magic had died with her husband and child.

It took two days for another fisherman’s wife to peek into their cottage, and a day after that for the midwife to reach them. It was a week before Katherine could sit up again. A week after that she was back on the road.

The journey was longer this time. Her body was damaged, though her life force was strong. She could hear her husband’s heartbeat in her own, feel the ghostly twinges of injury that mimicked the flutter kicks of the child she’d carried.

When she reached her father’s land, it was not yet dark. She walked past the river and the stables and the silent oak. She walked through the enchanter’s house, past startled servants, up to her father’s workshop. She threw open his door.

He was waiting for her, raven on his shoulder.

“My daughter returns.” His brow seemed untroubled but she knew him well, could read the rage in his tightening jaw.

“Did you fail to find your fortune?” he said. “Do you expect me to take you back? To continue your teaching? You’ve lost your beauty. You’re dressed like a common fishwife. Your power is out of practice.”

She didn’t say a word. Lying beneath the corpses of her husband and child, she’d worked out the shape of her curse, and knew who’d given it to her.

She took a knife and ran it over her throat.

That hungry, life-seeking piece of her rushed at the enchanter. His color was high, his bones unbowed, he crackled with good health. But his life was a thing with no shadow: a hard, bright pebble, edgeless. Without the presence of death to cast it into relief, it could not be peeled away.

The house and its grounds hummed with people. Servants and children, the new wife the enchanter had taken in Katherine’s absence, the baby he’d put in her belly. But they were too far away. Nearer to Katherine, and so imbued with magic by its master that its life shone with an unnatural light, was the raven.

Black-feathered, tarry-eyed, its years elongated by its covenant with the enchanter, the bird hopped on one foot. Katherine drank its life down.

All but the last little sip, which was tied to the bird with magic. Not as powerful as the spell that made Katherine unkillable, but nearly. That tiny piece of life folded itself up to the size of a seed, planting itself in the bird’s smallest claw.

When Katherine woke, her front was heavy with blood and the bird clung to her shoulder. She felt their shared life tilting between them like the liquid in a spirit level. It wasn’t enough.

Staggering to her feet, ignoring the enchanter, she ran from the room.

First they found a girl in a neat kerchief. A shriek jerked out of her at the sight of Katherine, bleeding, weak, and wild, her arm weighed down by the raven.

“Go,” Katherine whispered, and the bird obeyed. In a flash of feathers it stole the girl’s life, its talons flexing and Katherine weeping with relief as their two bodies, hers and the raven’s, were filled with it.

The enchanter’s deathless daughter made her way through his house. By the end of it she glowed with stolen life, her skin plumped like a pastry and her hair blazing red for the first time since she was a girl. She held the bird against her breast like a baby as she returned to her father’s room.

He’d heard the music of massacre and done nothing. All his long lifetimes cosseted by magic had made him weaker instead of strong. Katherine looked down at the fearsome enchanter who cowered before her.

“I spoke with Death when I was below. As my body tried to take your life, I petitioned him to help me, to kill you one way or another. And he told me something I wasn’t wise enough to see.”

“What—” The old enchanter—for he was, despite his youthful face, very, very old—swallowed dryly. “What did Death tell you?”

“That there are things worse than dying.”

Fed on the strength of many, the girl and her raven descended on the enchanter and tore him into living pieces, as many pieces as years he’d had of ill-gotten life.

Ever after Katherine kept a piece of her father hanging at her belt—his left eye, rolling in its pouch, seeing nothing. Her bird she carried in a cage, loosing it when she felt the life in her faltering, for she had work to do: stealing the lives of arrogant men, and those who would tangle the threads of magic.

Excerpted from Tales From the Hinterland, copyright © 2020 by Melissa Albert.